To truly leverage the immense capabilities of the Automatic Identification System (AIS), we must embark on a deep dive into the heart of its operations. At its most fundamental level, AIS operates by leveraging VHF radio frequencies which carry packets of data through the airwaves over a maritime domain. These packets deliver a digital trove of information, including some of the most critical aspects of a vessel’s situation and intentions. Such data isn’t only broadcast indiscriminately; AIS systems are also actively receiving similar packets from other ships in range, which is then compiled into a coherent picture of real-time maritime traffic conditions.

Central to the AIS operation is the Maritime Mobile Service Identity (MMSI), a nine-digit number allotted to each AIS system that uniquely identifies the vessel carrying it. Just as a car carries a unique license plate, the MMSI allows a ship to be recognized and tracked individually amidst a sea of traffic. It not only narrows down to the name and flag state of a ship but may also reveal ships in a specific company’s fleet or a particular type of service.

Each vessel’s AIS device sends updates, which include the ship’s current geographic coordinates marked with a time stamp. Experienced mariners understand the importance of this feature: by analyzing the progress of these time-stamped positions, it’s possible to determine a vessel’s heading and rate of turn, as well as detect any sudden changes in its navigation patterns.

Vessels aren’t merely points on a map—they have activity and intent. AIS data conveys this through navigational status indicators, reliably informing others of what the ship is doing: whether it’s anchored, moored, under power, or in a special condition like restricted maneuverability. Such statuses are indispensable for understanding the operating context of the vessels within range.

Vessels aren’t merely points on a map—they have activity and intent. AIS data conveys this through navigational status indicators, reliably informing others of what the ship is doing: whether it’s anchored, moored, under power, or in a special condition like restricted maneuverability. Such statuses are indispensable for understanding the operating context of the vessels within range.

Continuous broadcasting of a vessel’s speed and course over ground enables other seafarers to predict where that vessel will move next, critically important for avoiding mishaps in busy seaways. These movements can be calculated to deduce future positions, given no corrective actions are taken, which allows for proactive collision avoidance.

AIS also transmits details about a vessel’s dimensions, current load condition, type of cargo being carried, and sometimes even the destination and Expected Time of Arrival (ETA). This level of detail supports an enhanced appraisal of what a ship is capable of in terms of maneuverability and helps in understanding how it will likely behave in crossing situations, overtaking scenarios, or congested channel approaches.

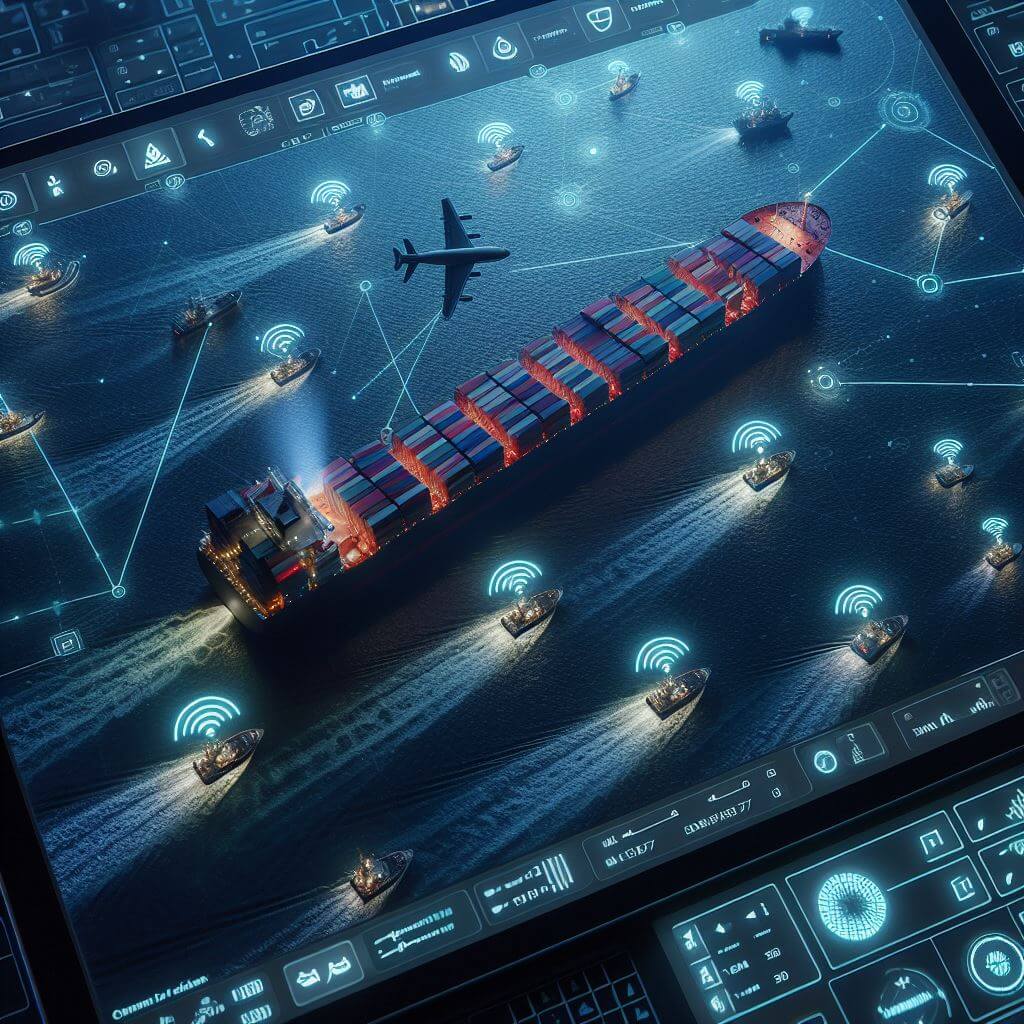

Through ongoing advancements in satellite technology, the reception of AIS signals has transcended from being an exclusively near-shore, line-of-sight communication to a global tracking and monitoring system with space-based AIS receivers. The broadening reach of AIS enables vessels and monitoring stations anywhere in the world to access near-real-time information regarding ship movements, contributing to a more connected and informed maritime community.

Decoding the Dots and Lines – Analyzing AIS Data on a Display

The ability to accurately interpret AIS data as it plays out across a ship’s display or chart plotter is a critical skill that the captain and crew must hone to ensure navigational excellence. With every seafaring vessel emitting a trove of information, the maritime display becomes a bustling tableau of symbols, each telling a tale of direction, intention, and potential interaction.

The time-stamped AIS data transmits onto displays, painting a vivid scenario of the marine traffic situation. Each vessel is represented by a symbol, conventionally shaped according to the type of vessel—cargo, tanker, towing, etc.—granting the observer an immediate visual cue to each ship’s role on the water. Alongside these visual identifiers, a vector, or heading line, extends from each vessel’s symbol, indicating the immediate direction of travel and offering a foretelling of where it is headed in the short term. By comparing the length and angle of one ship’s vector with another’s, navigators assess the possibility of crossing paths or converging courses, which could necessitate evasive action.

The true mastery of AIS data interpretation on a display resides not only in understanding what each ship is doing at the current moment but also in predicting with accuracy where each vessel will be minutes or even hours into the future. This forward-thinking analysis is fundamental to proactive navigation. Mariners must be able to extrapolate the motion vectors and determine the Closest Point of Approach (CPA) and the Time to Closest Point of Approach (TCPA) metrics with precision. The CPA is an arithmetical prediction of the nearest lateral distance between two vessels should their current courses remain unaltered, while the TCPA indicates when this point will be reached. Expert navigators pay careful attention to these figures, as they help determine whether risk of collision exists and when immediate action may be necessary. If either value falls within a predefined safety threshold, the mariner must be ready to communicate with other vessels and make course adjustments.

To deepen their interpretation, experienced mariners often overlay AIS data on top of additional navigational information such as electronic nautical charts (ENCs) and radar imagery. By correlating the AIS-derived positions of vessels against the static chart data of navigational hazards, water depths, and traffic separation schemes, navigators can enhance their understanding of the evolving traffic situation in the context of the local geography. Integration with radar data adds another dimension to this maritime mosaic. Radar can detect not only other ships but also small vessels, buoys, and other floating objects that may not be AIS-equipped. By synchronizing radar overlays with AIS signals on the chart display, navigators bolster their situational awareness with a more comprehensive view of their surroundings, including potentially uncharted threats.

In the grand synthesis of AIS signals upon the digital display, there lies both potent insight and the potential for deception. Navigators take heed that electronic systems, however sophisticated, can occasionally fail or provide erroneous data. They know to underpin their trust in technology with a layer of professional skepticism, always prepared to cross-verify AIS information with visual confirmations, radar echoes, and even crew reports from the deck. Such vigilance against over-reliance on AIS data is underscored in areas of high traffic density, close-quarter maneuvering, or during periods of increased navigational challenges such as poor weather conditions. In these scenarios, the navigator’s role becomes even more crucial—reminding us that while AIS is indeed a remarkable aid to safe passage through treacherous seas, it serves as a supplement, not a substitute, for the seasoned mariner’s wisdom and prudence.

Navigational Use and Safety Precautions in AIS Interpretation

The AIS is an indispensable component of maritime safety, expanding situational awareness and aiding collision avoidance. It allows vessels to see beyond the line of sight and through inclement weather, but as with all technology, it has its limitations. Therefore, the mariner’s judgment remains irreplaceable. Mariners should remain alert to the AIS system’s potential data inaccuracies due to factors like signal collisions, transmission delays, or incorrect data entry by the vessel crew. Contrasting AIS data with radar signatures and visual confirmation is wise. When discrepancies arise, the most reliable source should take precedence, often visual confirmation and active radar plotting.

Understanding patterns of vessel movement in particular areas can enable mariners to anticipate the actions of other vessels, which is particularly valuable in congested shipping lanes or near ports. This broader comprehension can lead to proactive, rather than reactive, navigation decisions that can enhance safety margins and make for a more orderly sea passage.

Navigators should be well-versed in the international regulations that govern AIS use and vessel responsibilities. Knowing who is the stand-on vessel, who should give way, and what maneuvers are expected of each vessel in any given scenario remains crucial, as AIS is but one tool in a vast array of navigational aids.